Great Marketers of the Industrial Revolution

By some historians’ measure, after the discovery of agriculture, the Industrial Revolution is the most important event in the history of civilization. It introduced the modern capitalist economy, established Great Britain as the world’s most powerful empire, accelerated European colonialism, reopened trade routes to Asia and the Middle East, and turned America into a legitimate state power on the global stage. It also destabilized age-old political structures, transformed cities into smoggy, disease-filled dystopias, prompted violent revolutions, and radically altered day-to-day life for people across the world, for better and worse.

But for those able to capitalize, the Industrial Revolution was an unprecedented business opportunity – and resourceful businessmen (mostly men) did very well. Because of its capitalist foundation, the Industrial Revolution was also the first time in history marketing and advertising were practiced on a large scale. Governments needed to publicize their new canals and railroads; craftsmen needed to promote their affordable textiles; engineers needed to showcase their inventions as superior to old models and current competitors.

So the salesman was born.

…Or at least a sort of salesman. No one featured below is a marketer in the traditional modern sense – several might regret the implication – but each figure used strategies still practiced today to appeal to consumers, audiences, investors, and fellow citizens.

Josiah Wedgwood, 1730-1795

The starving artist is so ingrained in the popular imagination that its counterpart (the satiated artist?) is met with suspicion at best, rejection at worst. Art and commerce can never coexist, the thinking goes. There are purists, and there are sellouts, and if anyone seems to challenge that binary, well, they’re probably the latter disguised as the former.

Of course, that’s nonsense. Plenty of accomplished artists have doubled as successful entrepreneurs — and perhaps none more than Josiah Wedgwood, a professional potter credited as one of the founders of modern marketing. After years of training and apprenticeship, Wedgwood had mastered his craft and began to receive commissions from British nobility, including Queen Charlotte. Not satisfied with patronage alone (as a Renaissance craftsmen might’ve been), Wedgwood capitalized. He set up showrooms in rapidly expanding cities, including Liverpool and Dublin, where eager middle-class consumers could come to catch a glimpse at the “Queen’s Ware”: teapots, plates, vases, and other tableware, sealed with royal approval. Once industrialized manufacturing reduced his pottery’s cost, Wedgwood used direct mail campaigns, money back guarantees, free delivery services, catalogues, and other now familiar strategies to market his products in Europe and America. In a feature for the BBC, one British historian names Wedgwood “above all others a hero of the Industrial Revolution.” True: but a marketing whiz, too.

FEATURED ONLINE PROGRAMS

-

>Master’s in Marketing Communications

The Marketing Communication master’s concentration prompts you to analyze consumer behavior, conduct market research, and engage the power of brands and messages in order to develop powerful digital marketing strategies. Evaluate various tactics, measure their effectiveness, and explore the intricacies of working with or in complex, multi-functional teams to execute compelling marketing campaigns.

Highlights:

- Top 100 university

- 100% online

- No GRE

Matthew Boulton, 1728-1809

One half of the famed steam engine duo, Matthew Boulton provided the business plan that brought Watt’s technology to mass market. (Incidentally, Boulton only filled the role after Watt’s previous business partner, John Roebuck, defaulted on a debt to Boulton.) For several years, Watt’s patent remained undeveloped. Other steam engines were already being used to pump water out of mines, and while Watt’s more powerful model was well-known, he hadn’t demonstrated its commercial viability, or shown much interest in doing so. Watt drummed up public interest, lobbied parliament to extend the patent, and secured crucial business partnerships through a series of demonstrations and calculated publicity stunts. Boulton also leveraged product differentiation, celebrity endorsements, and planned obsolescence to build his fortune, eventually earning a contract to produce Britain’s coinage. A showman and a keen psychologist, Boulton told James Boswell, who was visiting his renowned Soho Mint, “I sell here, sir, what all the world desires to have—POWER.”

Daniel Defoe, 1660-1731

Defoe is synonymous with Robinson Crusoe and, to a lesser extent, Moll Flanders, but his novels’ fame have actually obscured Defoe’s other significant work, from political pamphlets (which landed him in prison) to essays in verse and eccentric nonfiction tracts, like the provocatively titled Political History of the Devil. More to the point, Defoe was a pioneer in business and economic journalism. In addition to The Complete English Tradesman, he published in-depth guides on Scottish, French, and Indian trade that effectively served as market research, highlighting the superiority of British business practices and stressing the importance of commerce to imperial expansion and domestic prosperity.

Now, we’re cheating a bit: Defoe died just before the Industrial Revolution began. But he helped lay its groundwork and developed a national business literacy that entrepreneurs like Boulton and Wedgwood would put to use later.

Alexander Turney Stewart, 1803-1876

A. T. Stewart realized that consumers are intelligent: not a revolutionary concept, but one that earned him a lot of money. Instead of setting up his dry goods store on Broadway, where rents were expensive and store owners jousted for customers, Stewart opened up across City Hall Park in a relatively undeveloped, unassuming block, betting that if prices were low enough — of if he could “obtain wholesale trade to undersell competitors” – customers would find him. And he was right. Customers came and came again, in part because of the store’s friendly, personal service, but also on account of Stewart’s savvy sales tactics. Already short on space, he placed extra merchandise on the sidewalk, and for several years, he didn’t advertise or even put up a sign for his store: an early case of the brandless brand.

Once A. T. Stewart & Co. had outgrown its modest original storefront, the “Marble Palace” was erected, a massive cast-iron building on Broadway and 10th Street (still standing), known among retailers as the “cradle of the department store.” Stewart also opened up retail to women and began receiving letters from across the country by women eager to purchase the latest in fashion. This, too, was an opportunity. Stewart set up a mail order business, which pocketed half a million dollars in the first year and prompted Sears, Montgomery Ward, and Spiegel’s to set up their own mail orders.

Karl Marx, 1818-1883

Marx the marketing maven? Ok, maybe a stretch, but a noteworthy case. Though Marx himself trawled economics, political theory, philosophy, history, and sociology to develop his revolutionary system of thought, he was a subtle psychologist as well (like others on the list). Yes, he thought communism’s success was inevitable, the natural outcome of capitalism’s – and the industrial revolution’s – imminent failure, but he also understood that communism required organization and mobilization, and communism could never be achieved if no one understood it. So he co-authored a short but handy pamphlet.

The most famous sentence in The Communist Manifesto is the first one: “The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.” In journalism, it’s called a lede; in pop music, the hook. Regardless, that first sentence says as much about Marx’s understanding of humans as it says about his worldview. It’s a thesis, but more important, it’s a story, with characters and a defining conflict; simple and straightforward, but also compelling: the reader has to know more. How does the struggle play out? How will it end? The other bit of genius was the book’s timing. Published in 1848, just as revolutions began to erupt across Europe, Marx’s argument was ripe – and almost self-evident. The status quo did not appear sustainable.

Still, in his lifetime, Marx remained obscure, and The Communist Manifesto didn’t sell many copies for another thirty years, when the Paris Commune reignited interest in revolutionary politics. Marx and Engels wrote many articles, essays, and books during that span, including Das Kapital, but the manifesto remains communism’s founding document for its clarity, conciseness, and (ironically) sound business strategy: state a problem and provide the solution.

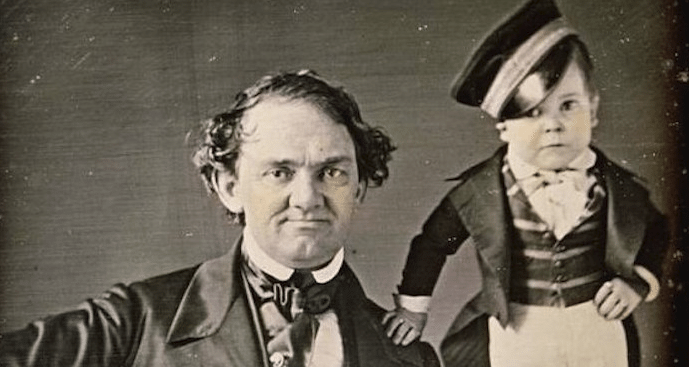

P. T. Barnum, 1810-1891

Unsurprisingly, the greatest showman on earth was a master promoter. Born at the beginning of the 19th century, P. T. Barnum didn’t begin his famous circus until 1871, having already owned several businesses, worked as a funhouse performer, managed theaters, produced plays, created the first American aquarium, and generally established himself as a restless provocateur and attention-seeker. By the time the circus opened, Barnum was a household name, and he used his reputation – influence? celebrity? brand? – to lure audiences nationwide, all of whom believed in his promise to deliver something utterly new and wild. Never known for integrity, he was right on that point.

Circus act aside, Barnum’s marketing strategy was groundbreaking. He ran provocative newspaper ads, draped banners over whole buildings, and hired horse-drawn wagons that featured promotional posters and signs to parade New York’s jam-packed thoroughfares. As the executive director of the Barnum Museum says, “While there certainly was advertising and promotion before Barnum came along, he took that science to new and never-before seen levels.” One hesitates to ask, but…never-since surpassed?

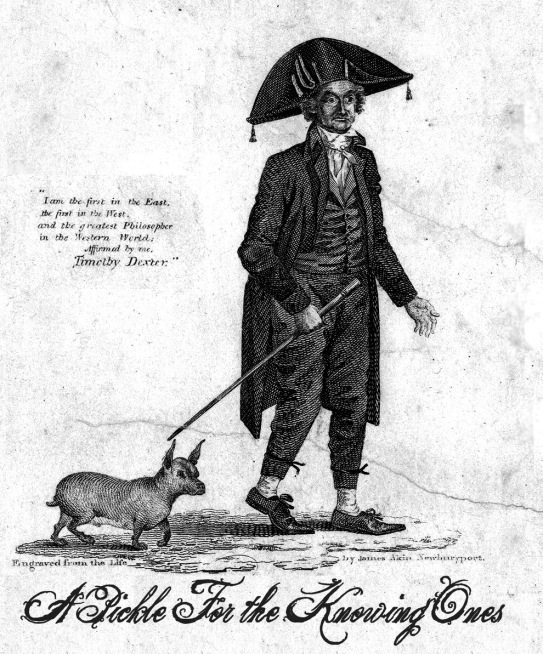

Lord Timothy Dexter, 1747-1806

If P. T. Barnum amassed a fortune through cunning, know-how, and self-aware circus acting, then Timothy Dexter might be his opposite: a clueless charlatan and dilettante, the kind of eccentric that Barnum might’ve liked to place on exhibit, but who stumbled into a colossal sum of money after a series of improbable, even farcical business decisions.

Dexter’s first unlikely windfall arrived in the 1790s. Against all common sense, he had invested his (and his wife’s) life savings in the Continental dollar – a currency without any value – during the Revolutionary War. (He was ostensibly aping wealthy neighbors, but they had invested as a sign of wartime solidarity, and even then didn’t flush away their savings.) After the war ended, the Continental Congress worked to negotiate and ratify the Constitution, which, much to everyone’s surprise, included a provision that allowed Continental dollars to be traded in for treasury bonds. Suddenly, sans any apparent logic, Dexter was very rich. But he didn’t stop there. Among Dexter’s divers schemes include selling warming pans rebranded as ladles to West Indies plantation owners (at a 79% markup), cornering the whale bone market (and selling at 75% markup), and unloading 21,000 bibles (for $47,000) on the threat that anyone who bought a non-Dexterine edition would go to hell.

Some of Dexter’s successes were preposterously lucky: for instance, the time a trader fooled him into trying to sell coal in Newcastle, a mining town, only for the mine to be on strike and Dexter sell his coal at, per usual, a significant markup. But the self-styled Lord’s business record speaks for itself, in spite of itself, and Dexter has achieved cult fandom. Are his methods replicable? Ethical? No. Then again, it takes a singular character to become “the Paul Bunyan of American commerce.”